Up Next- Orionid Meteors

The dark skies of the Gunflint Trail are perfect for watching meteor showers. Up next are the Orionids!

Look for Orionid meteors this month

Details on the annual Orionid meteor shower. How and when to watch. In 2017, the peak morning is probably October 21. But start watching now, before dawn!

Have you seen any meteors streaking across the sky this month? If they are coming from the northern sky, they might have been Draconids, whose peak has passed. But they also might be meteors in the annual Orionid meteor shower, which is now building to a peak on the morning of October 21, with no moonlight to ruin the show. Orionid meteors fly each year between about October 2 to November 7. That’s when Earth is passing through the stream of debris left behind by Comet Halley, the parent comet of the Orionid shower. With the moon a thin waning crescent in the morning sky now, it’s a good time to start watching for Orionids. How many meteors might you see on the peak night, or in the nights leading up to the shower? Follow the links below to learn more:

What are the prospects for this year’s Orionid shower? The word shower might give you the idea of a rain shower. But few meteor showers resemble showers of rain. The Orionids aren’t the year’s strongest shower, and they’re not particularly known for storming (producing unexpected, very rich displays). But – from a dark location, in a year when the moon is out of the way at the peak (as is the case in 2017) – you might reliably see 10 to 20 meteors per hour at the peak.

The Orionids are known to be fast and on the faint side, but can sometimes surprise you with an exceptionally bright meteor that might break up into fragments.

As is usual for most (but not all) meteor showers, the best time to watch the Orionids is in the dark hours before dawn.

Again, the peak morning is likely October 21. Do start watching in the days ahead of the peak, though. You might catch an Orionid meteor or two before dawn over the coming days.

How will you know it’s an Orionid? You’ll know because it’ll come from the shower’s radiant point. More about that below.

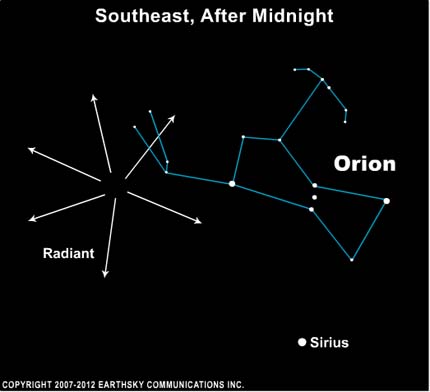

The Orionids radiate from a point near the upraised Club of the constellation Orion the Hunter. The bright star near the radiant point is Betelgeuse.

Where do I look in the sky to see the Orionids? Meteors in annual showers are named for the point in our sky from which they appear to radiate. The radiant point for the Orionids is in the direction of the famous constellation Orion the Hunter, which you’ll find ascending in the east in the hours after midnight. Hence the name Orionids.

You don’t need to know or be staring toward Orion to see the meteors. The meteors often don’t become visible until they are 30 degrees or so from their radiant point – and remember, they are streaking out from the radiant in all directions. They will appear in all parts of the sky.

However, if you do see a meteor – and trace its path backward – you might see that it comes from the Club of Orion. And, if so, that meteor will be an Orionid. You might know Orion’s bright, ruddy star Betelgeuse. The radiant is north of Betelgeuse.

So … in which direction do you look? No particular direction. It’s best to find a wide-open viewing area. Sometimes friends like to watch together, facing different directions. When somebody sees one, they can call out “Meteor!”

Brian Brace caught the 2014 Orionid shower and wrote, “A few hours into our adventure, we’d witnessed only a few meteors flying by. But right before I took the camera down this huge fireball streamed across the northeastern sky. That one meteor made the whole night worth it.”

What are meteors, anyway? Meteors are fancifully called shooting stars. Of course, they aren’t really stars. They’re space debris burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

The Orionid meteors are debris left behind by Comet Halley. The object in the photo above isn’t a meteor. It’s that most famous of all comets – Comet Halley – which last visited Earth in 1986. This comet leaves debris in its wake that strikes Earth’s atmosphere most fully around October 20-22, while Earth intersects the comet’s orbit, as it does every year at this time.

Particles shed by the comet slam into our upper atmosphere, where they vaporize at some 100 kilometers – 60 miles – above the Earth’s surface.

The Orionids are extremely fast meteors, plummeting into the Earth’s atmosphere at about 66 kilometers – 41 miles – per second. Maybe half of the Orionid meteors leave persistent trains – ionized gas trails that last for a few seconds after the meteor itself has gone.

For me … even one meteor can be a thrill. But you might want to observe for an hour or more, and in that case the trick is to find a place to observe in the country. Bring along a blanket or lawn chair and lie back comfortably while gazing upward.

Halley’s Comet, perhaps the most famous of all comets, is parent of both the Eta Aquarid meteor shower in May and October’s Orionid meteor shower. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: In 2017, the Orionid meteor shower is expected to rain down its greatest number of meteors on the morning of October 21. You might also see a meteor or two each hour on moon-free mornings leading up to the peak.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.