Space Stuff- meteors and moons

From Space Weather Website!

On October 5, the Harvest Moon

Tonight – October 5, 2017 – that full moon you’ll see ascending in the east after sunset is the Northern Hemisphere’s Harvest Moon.

Over the years, we’ve seen lots of informal uses of the term Harvest Moon. Some people (in the Northern Hemisphere) call the full moons of September and October by that name. And that’s fine. For the few months around the autumn equinox – both September and October for us in the Northern Hemisphere – the time of moonrise is close to the time of sunset for several evenings in a row, around the time of full moon. It’s as if there are a few full moons in a row during each autumn month.

Astronomers are scientists, though, and it’s no surprise that, to them, the term full moon or the name Harvest Moon means something very specific. To astronomers, the Harvest Moon is the full moon closest to the September equinox, and full moon comes at the instant when the moon is 180o from the sun in ecliptic – or celestial – longitude.

In 2017, this equinox took place on September 22.

The closest full moon to the autumn equinox reaches the crest of its full phase on October 5 at 18:40 UTC. For us in the continental U.S., the moon turns precisely full during the daytime hours on Thursday, October 5. By U.S. clocks, that full moon instant comes at 2:40 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time, 1:40 p.m. Central Daylight Time, 12:40 p.m. Mountain Daylight Time, 11:40 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time, 10:40 a.m. Alaskan Daylight Time and 8:40 a.m.Hawaiian Standard Time.

But don’t worry too much about the instant of full moon, or the time on your clock, or even where you are on the globe. No matter where you live worldwide, you’ll see a full-looking moon shining from dusk until dawn on the night of October 5.

Tonight’s October Harvest Moon rises in the east around sunset, climbs highest up around midnight and sets in the west around sunrise. At the vicinity of full moon, the moon – as always – stays out all night long.

Is tonight’s moon the Harvest Moon? It sure is – at least for the Northern Hemisphere!

Meanwhile, for the Southern hemisphere, this is the first full moon of spring.

Day and night sides of Earth at the instant of full moon (2017 October 5 at 18:40 Universal Time) via Earth and Moon Viewer. The shadow line at left represents sunset October 5, and the shadow line at right depicts sunrise October 6.

What’s the big deal about the Harvest Moon? Why are the full moons special in autumn? Around the time of the autumn equinox, the ecliptic – or the path of the sun, moon, and planets – makes a narrow angle with the horizon at sunset.

Every full moon rises around the time of sunset, and on average each successive moonrise comes about 50 minutes later daily. But, on September and October evenings – because of the narrow angle of the ecliptic to the horizon – the moon rises sooner than the average.

So, instead of rising 50 minutes later in the days after full moon, the waning gibbous moon might rise only 35 minutes later, or thereabouts, for several days in a row (at mid-northern latitudes). At far northern latitudes – like at Fairbanks, Alaska – the moon rises about 15 minutes later for days on end.

That fact was important to people in earlier times. For farmers bringing in the harvest, before the days of tractor lights, it meant there was no long period of darkness between sunset and moonrise for several days after full moon. And that meant farmers could work on in the fields, bringing in the crops by moonlight. Hence the name Harvest Moon.

At our mid-northern latitudes, watch for the Harvest Moon to shine from dusk until dawn for the next few to several days.

Bottom line: Enjoy the 2017 Harvest Moon!

All you need to know: Draconids in 2017

The Draconids are best seen in the evening hours. In 2017, a bright waning gibbous moon will interfere, but still … give it a try!

Where is the radiant point of the Draconid shower, and how many Draconids will I see?

Can I see the Draconids from the Southern Hemisphere?

Origin and history of Draconid meteors

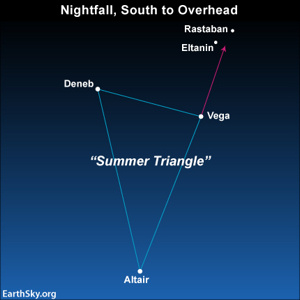

Draconids radiate from near the Dragon’s Eyes: the stars Eltanin and Rastaban. Familiar with the Summer Triangle? Draw an imaginary line from Altair through Vega points to them.

Where is the radiant point of the Draconid shower, and how many Draconids will I see? Unlike most meteor showers, the Draconids are best seen in the evening, instead of before dawn. That’s because the winged Dragon, the shower’s radiant point, flies highest in the sky at nightfall.

These extremely slow-moving Draconid meteors, when traced backward, radiate from the head of Draco the Dragon, near the stars Eltanin and Rastaban.

However, you don’t have to locate Draco the Dragon to watch the Draconids, for these meteors fly every which way through the starry sky.

Usually, this meteor shower offers no more than a handful of languid meteors per hour, even at its peak. Plus, in 2016, the waxing crescent moon will somewhat intrude on this year’s show. But this shower has been known to rain down hundreds or even thousands of meteors in an hour. And in fact it’s the history of this shower that makes it so interesting. See the history section, below.

No outburst is predicted for this year, but then, you never know for sure. Remember – no matter where you are on Earth – the radiant for this meteor shower is highest up in the evening. Watch for the Draconids, starting at nightfall on October 7 and 8.

Simply find a dark, open sky away from artificial lights. Plan to spend a few hours lounging comfortably under the stars. Bring along a reclining lawn chair, have your feet point in a general north or northwest direction and look upward.

If you don’t know your cardinal directions, just lie down and look upward. Enjoy!

More about the Draconid meteor shower radiant point here.

Here’s a more detailed view of the radiant point of Draconid meteor shower. It’s highest in the north at nightfall in early October.

Can I see the Draconids from the Southern Hemisphere? It’s possible you might see some Draconid meteors around the shower’s peak, if you’re in the Southern Hemisphere. But if you’re so far south that the radiant point in the constellation Draco doesn’t rise above your horizon, or rises only briefly, the meteors will be very few to nonexistent.

As seen from the Southern Hemisphere, you would have to be rather close to the equator in order to see Draco’s stars. Suppose you live in northern Australia – say Darwin, in northern Australia – which is at 12 degrees S. latitude. If so, you’d be able to see the stars Rastaban and Eltanin very close to your north-northwest horizon at nightfall in early October (given an unobstructed northern horizon). These stars would set at fairly early evening, and you wouldn’t see the head of Draco again until nightfall the following evening.

Why early evening? It’s because, no matter where you live worldwide, the head of Draco reaches upper transit (its highest in your sky) at around 5 p.m. local time in early October.

Thus from latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere – even those as far north as northern Australia – you would have a very narrow window for seeing meteors. If you’re in the Southern Hemisphere, and you’re really wanting to see a Draconid, try looking as soon as it gets really dark on October 7 and 8, and don’t expect much.

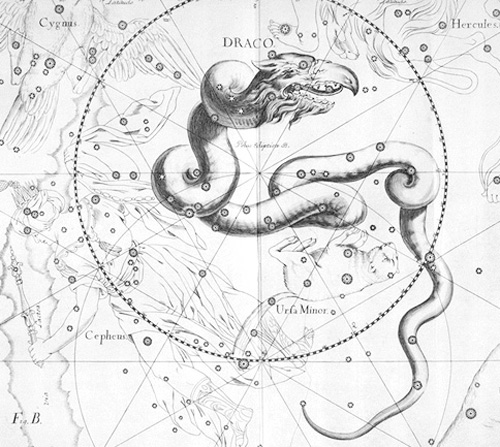

Draco as depicted in an old star altas. The constellation of the Dragon winds around the sky’s north pole.

What is the origin and history of the Draconid meteors? This annual meteor shower results when the Earth in its orbit crosses the orbital path of Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner. Debris left behind by this comet collides with the Earth’s upper atmosphere, to burn up as Draconid meteors.

This comet has an orbital period of about 6.6 years. It’s about 6 times more distant at its farthest point from the sun than at its nearest point. At aphelion – its most distant point – it’s farther out than the planet Jupiter. At perihelion – its closest point to the sun – it’s about the Earth’s distance from the sun.

Most meteors in annual showers aren’t named for their parent comets, but instead for the constellation from which they appear to radiate, in this case Draco the Dragon.

Draco’s meteors, however, defy convention by sometimes also being called the Giacobinids, to honor the role this comet played in the history of astronomers’ understanding of what meteors actually are.

Michel Giacobini discovered this comet on December 20, 1900, and thus the comet received his name. Another sighting in 1913 added Zinner to the comet’s name, which thus became 21P Giacobini-Zinner. Astronomers in the early 20th century thought that meteors and comets were related, so of course they tried to link various comets to the spectacular showers of meteors that sometimes rain down in Earth’s sky.

Comet 21P Giacobini-Zinner was a particularly tempting object about which to make predictions. Remember, it returns every six years, and its closest point to the sun is about the same as Earth’s distance.

What’s more, Comet Giacobini-Zinner did not disappoint the astronomers.

The Draconid meteor shower produced awesome meteor displays in 1933 and 1946, with thousands of meteors per hour seen in those years. Read a more complete account of historical predictions about Giacobini-Zinner and its meteor showers here.

In October 2011, people around the globe saw an elevated number of Draconid meteors, despite a bright moon that night. European observers saw over 600 meteors per hour in 2011.

No one is expecting that this year, but you never know.

The relationship between 21P Giacobini-Zinner and its meteors – so studied and discussed in among professional astronomers in the early 20th century – probably explains why the Draconid meteor shower sometimes goes by the name Giacobinids

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.